Author(s): Wohlgemuth, Walter A. | Dießel, Linda

Author(s): Wohlgemuth, Walter A. | Dießel, Linda

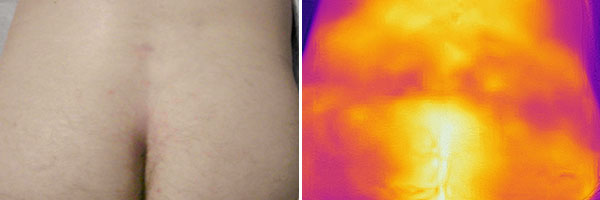

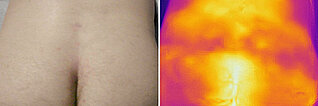

33-year-old patient who feels healthy. However, he has had recurrent pain and left lumbar swelling for almost 2 years. In an MRI to exclude a herniated disc, an unclear tumor is found. Presentation for biopsy and further clarification of the lesion. Infrared thermography (right) shows no local warmth or change in perfusion in the area of the pain. Currently no swelling or skin discoloration in the photograph (left).

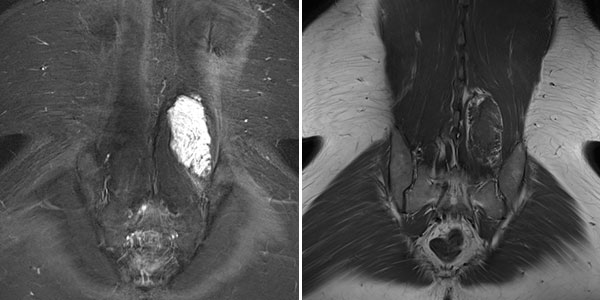

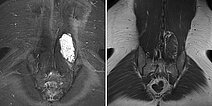

The lesion is very clearly visible in the MRI in coronal plane. In the T2-weighted sequence with fat saturation (left), the lesion is highly hyperintense (white). In the non-enhanced T1-weighted sequence (right), it is virtually isointense to the surrounding back muscle. Note here the fatty tissue visible marginally in the lesion, hyperintense in T1 weighting.

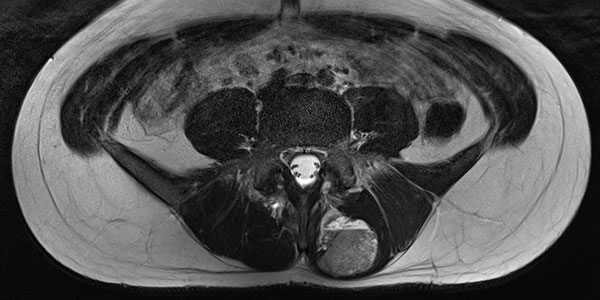

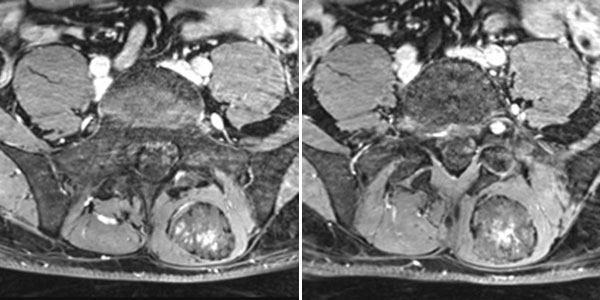

In the axial T2-weighted MRI sequence, the lesion is located in the erector spinae back muscles. Classic fluid-fluid level due to gravity-induced sedimentation effects with the patient lying still in the supine position in the MRI unit.

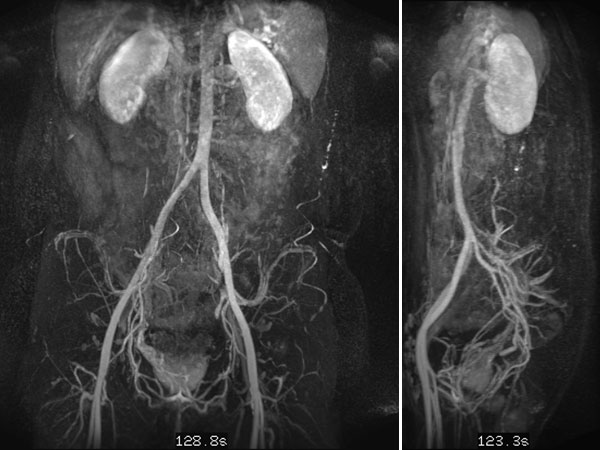

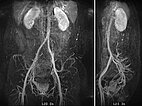

In dynamic contrast-enhanced MR angiography (late phase over 2 min after contrast administration, left coronal and right sagittal), the lesion shows no contrast enhancement or increased vascularization. It is practically invisible.

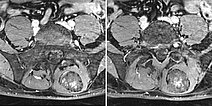

In the axial, fat-saturated T1-weighted images after contrast medium administration, an initially inhomogeneous accumulation of contrast medium in terms of contrast pooling occurs only slowly and incompletely. This is also relatively typical of a venous malformation.

An ultrasound-guided punch biopsy with a thin 16-gauge biopsy needle is performed immediately afterwards. Only minor bleeding occurs during needle biopsy, which is quickly stopped by compression. Note the dark red tissue fragment obtained, which macroscopically looks almost like a thrombus but consists of the blood-filled dysplastic cavities of the venous malformation.

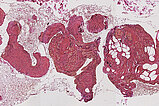

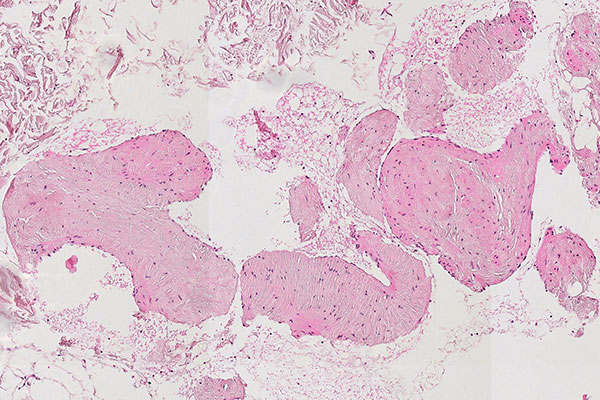

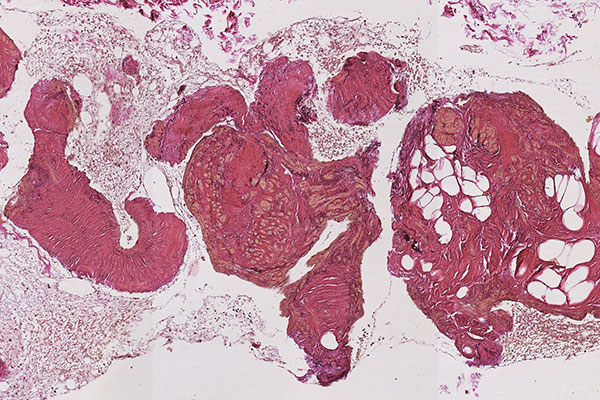

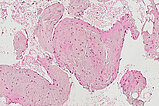

Histopathological section; hematoxylin & eosin (HE) stain, 90x magnification of the punch cylinder. Punch cylinder showing parts of venous malformation with densely packed, irregularly configured large-caliber venous vessel parts. These do not appear tubular as in a normal mature vessel, but as if the vessels are "everted". The lumen looks solid and blood is all around the outside.

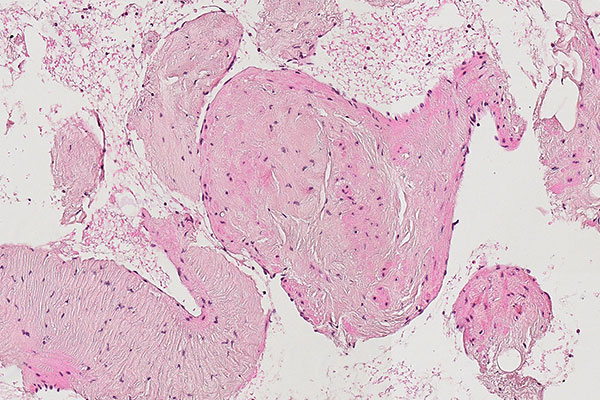

Histopathological section; hematoxylin & eosin stain (HE), 160x magnification of the punch cylinder. Here it is clear to see that the irregular, blood-filled spaces of the venous malformation are not solid, but are "voids" partially filled with erythrocytes. The endothelial lining corresponds to the outer border of the visible lesion.

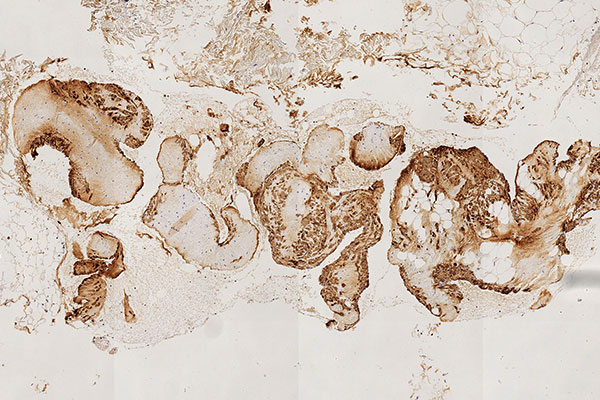

Histopathological section; CD31 stain for specific staining of vascular endothelial cells, which then stain dark brown. 80x magnification of the punch cylinder. This proves that the outer cellular boundary of the visible lesion corresponds to blood vessel endothelia.

![[Translate to English:] Intramuskuläre venöse Malformation Histopathology CD31 stain – Intramuscular venous malformation](/fileadmin/images/patientenbeispiele/44-vm-intramusk/f44-09-histopathologie-venoese-malformation-im.jpg)

Histopathological section; Elastica van Gieson (EvG) staining of collagen and connective tissue. 90x magnification of the punch cylinder. EvG connective tissue staining illustrates the dysplastic wall structure of the malformation with yellow-stained smooth muscle fiber tracts intermixed with red-stained connective tissue areas and interspersed delicate black elastic fibers. This structure is actually typical of venous vessels, but the irregular structure depicted here is atypical and indicates the malformed venous wall structure of the venous malformation.

Histopathological section; the immunohistological staining against smooth muscle actin (SMA) demonstrates the irregular, dysplastic wall structure of the vessels of the venous malformation particularly well. A normal, ordered smooth muscle wall structure is not present. The lesion is asymmetrically interspersed with irregular SMA-positive smooth muscle.

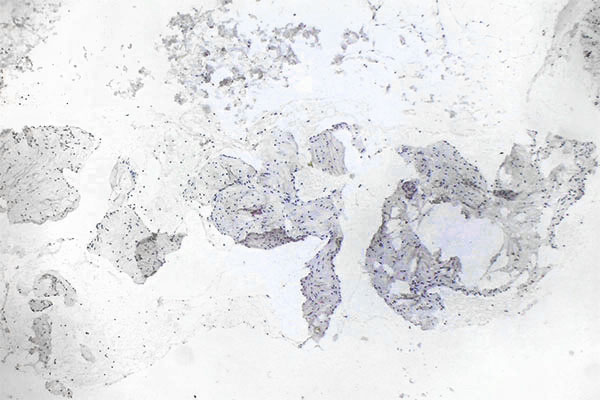

Histopathological section; immunohistological staining using MIB-1 for the Ki67 antigen is a classic stain to show the proliferation activity of a lesion. As a proliferation marker, Ki67 indicates all cells undergoing cell division in the broadest sense (outside the G0 phase in the cell cycle). Here, only very few actively dividing nuclei (here without mitotic spindles) are detectable as positive nuclear staining. Thus, a very low proliferation rate is an indication of a benign lesion.

The patient's history is typical: Having previously been healthy, the patient develops thrombophlebitis within a previously unrecognized venous malformation (VM). A subsequent MRI then reveals a clearly visible, large "tumor" that must be distinguished from a malignant lesion in terms of differential diagnosis.

Purely histopathological diagnosis of a lesion as a venous malformation under the microscope is hardly possible without corresponding clinical information and appropriate clinical referral. Nevertheless, there is good evidence that will characterize a venous malformation based on immunohistology and morphology. The venous malformation is a spongy, blood-filled lesion without any real solid parts, similar to a Swiss cheese with a lot of air (air holes = blood-filled cavities; cheese = dysplastic, venous wall structures). Thus, the actual dysplastic vein walls make up only a fraction of the volume in the overall blood-filled lesion and usually appear irregularly branched like a foxhole rather than tubular.

Immunohistochemical staining with CD31 (blood vessel endothelium) lining the lesion, and the irregular, sometimes patchy, asymmetric surrounding of smooth muscle cells (SMA stain) as well as evidence of atypical collagen and elastic fibers (EvG stain) distributed in the venous vessel wall make the diagnosis highly probable. Venous malformations show little proliferative activity (MIB-1). The histopathologically very similar-looking lymphatic malformation can be well differentiated by D2-40 (podoplanin) staining, which specifically stains only lymphatic vessel endothelia.

In most cases, histopathological workup of a venous malformation will not be necessary because the clinical appearance and imaging already suggest the diagnosis. If it is necessary, however, the diagnosis can be made by means of histopathology if the correct stains and principles set out here are applied. The patient was subsequently treated with bleomycin electrosclerotherapy.

Published: 2022

All images © Wohlgemuth/Dießel

![[Translate to English:] Intramuskuläre venöse Malformation Histopathology CD31 stain – Intramuscular venous malformation](/fileadmin/_processed_/a/4/csm_f44-09-histopathologie-venoese-malformation-im_86b69e7945.jpg)